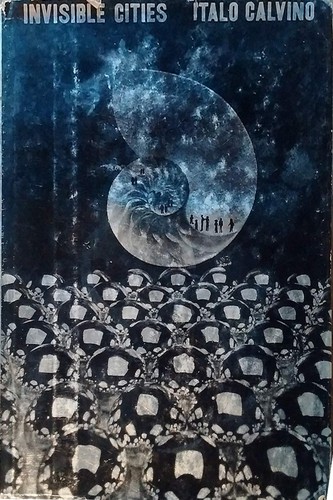

Thoughts on reading Invisibile Cities by Italo Calvino.

Our recollection of life is nothing more than an autobiographical history; an amalgamation of biased documentations of concrete events stored in the form of a memory. The conflict resulting from the human propensity for unlimited desires whilst operating with scarce resources is precisely where the augmentation of our memories occur. The failure of our memories to accurately represent events is addressed both in Calvino’s “Invisible Cities” and Kafka’s “In The Penal Colony”. In “Invisible Cities”, Calvino constructs two cities - Isidora and Zobeide - that address the conflict between memories and desires. In these two cities, Calvino utilizes time to agitate the conflict, as well as having time serve as the preeminent obstacle between the merging of memories and desires. “In The Penal Colony” addresses the conflict of desire and memories in a similar fashion. In the story, the officer of the penal colony is the victim of this conflict, which is exposed through the experience of the explorer, who witnesses a contradiction between how the officer and the townspeople remember the old commandment. Again, time is the agitator of the conflict, yet it is not just time that serves as an obstacle of resolution, but also the power of the officer and the inflated ego that power yields. As explored in both “Invisible Cities” and “In The Penal Colony”, memories often serve as an extra-factual history of past events, inundated with biases incubated by the present desires of those fortunate enough to narrate their own stories.

The city of Isidora is a city of memory, a fantastical city constructed by the youthful desires of old men. The fantasies of Isidora are polar, the city has no room for mundane realities. Yet Isidora is not a utopia, and in some sense, it is almost a prison. The city is built to house the ambiguous desires of young men, men who dream of perfection. Yet these architects are withheld from interacting with their creations, as they enter the city in an old age, rendering them as nothing more than mere bystanders. In recounting Isidora to the Kahn, Marco Polo comments on this plight, explaining that for the architects,

Desires are already memories (8)

What Polo’s commentary rests on is the fact that time is a barrier to realization of desires. However, the ambiguity of the architects of Isidora strikes a deeper vein. It is all old men who sit and watch the young go and live the desires of their youth. Yet if it is all old men who reminisce, then it is also all young men who share the same polar desires. And if that is the case, then none of the events of Isidora are histories, but merely dreams. And it is here that the contradiction lies. If desires are already memories, as Polo claims, then the memories of the architects of Isidora are not based on histories, but distorted by dreams. Isidora is a universal falsehood of a city: none who enter may ever truly live in Isidora, just as one who always desires perfection will never live it, no matter what their memories may say.

Zobeide is a city of desire, a monstrous city, constructed by masses of individual men who share a dream of chasing a beautiful woman through an unknown city. In hopes of obtaining the women, the architects augment the layout of the city from what was observed in their dreams, aiming to trap the woman. Marco Polo ends the rendition of Zobeide with the remark:

The first to arrive could not understand what drew these people to Zobeide, this ugly city, this trap (46)

Zobeide is a city constructed by pure desires, yet as time progresses, these desires erode, and all that is left is an empty memory. To this effect, Zobeide is a converse city of Isidora: here, desires do not overwhelm, but are engulfed by memory. This lack of desires may leave only reality in memory, but even this memory is false. Zobeide was built on desires, and thus any history without that fact is an inauthentic history. The expulsion of desires from memory has the same effect on the architects of Zobeide as the false memories of the architects of Isidora: easing the pain of unrealized dreams.

“In The Penal Colony” explores memory through the officer’s recollection of the colony’s past. Reminiscing to the explorer, the officer describes the olden days of execution, where

A whole day before the ceremony the valley was packed with people; they all came only to lookon; early in the morning the Commandant appeared with his ladies; fanfares roused the wholecamp (208)

In this memory, the gruesome and unjust execution is beloved by all, with immense admiration shown towards the officer and the Commandant. In this memory, the officer basks himself in the former glory of his absolute and unchallenged power, where tyranny was admired by layfolk. This memory is of course in stark contrast to what the explorer observes as the current state of the colony: archaic decay and uninspired tradition. The pathetic state of the officer is confirmed when the explorer leaves the colony, as he exits through the teahouse, where the soldier tells him:

The old man’s [Commandant’s] buried here … The officer never told youabout that, for sure, because of course that’s what he is most ashamed of (225)

Unlike the universally beloved Commandant of the officers memory, the real Commandant was abandoned by the members of the colony, people who could not even grant him the dignity of being buried in the churchyard. This reality is in conflict with the officer’s memory of the Commandant’s absolute and benevolent power, which was in turn absorbed by the officer. The officer knows that his power is meaningless if it is not accepted by his subordinates, an acceptance which the officer most desires. To reconcile this, the officer conjures false memories of a glorious past where his brutality is loved and the Commandment is revered, in which his ego is inflated to a point where he may distract himself from the disdain of all who interact with him. For the officer, the falsehood of his memories is necessary to render his life meaningful, for he is ashamed from the sham of his reality.

The misalignment between memory and history is explored in both Calvino’s “Invisible Cities” and Kafka’s “In The Penal Colony” through varying lenses. Yet all cases converge to an understanding that the biases of memories can be attributed to unattainable desires, a convergence that is dependent on the passage of time. All dream and all live, and it is in the difference of these two universal experiences where memory resides.